The Emperor Hiding in Plain Sight

Posted on 13 December, 2018

It is nearly a year since we began following art historian and provenance researcher, Silvia Davoli, in her quest to unearth the lost treasures of Strawberry Hill. In this eleventh instalment of our blog series a simple case of mistaken identity leads Silvia to discover a rare painting of a young Emperor Charles V, which Walpole never knew he possessed.

For years I have searched for Walpole’s hidden gems, tucked away in discreet corners of the globe in the lead up to the opening of the ‘Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill’ exhibition. I can still barely contain my joy at having restored over one hundred of his missing masterpieces to the gothic villa of Strawberry Hill House where they will remain on display until February 2019. In spite of this triumph, I refuse to cease my investigations. There is still so much work to be done and so many niches and empty walls of Walpole’s former home to fill with precious objects that remain at large.

It is this tenacity which powers my work as a provenance researcher even in the face of months of fruitless searching for obscure works identified by only a few lines in Walpole’s ‘Description of the Villa’.

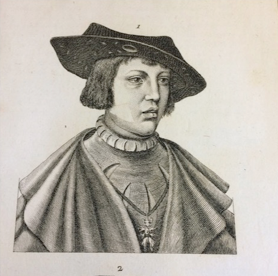

One such shadowy piece is a 16th century (ca. 1511) oil on oak portrait by Bernard Van Orley (1500-1558), which hung in the Holbein Chamber at Strawberry Hill. In Walpole’s 1784 Description, I read that he referred to the painting as ‘Portrait of Philip of Austria son of the Emperor Maximilian, in the Style of Holbein’. It seems he identified the sitter as Philip of Austria based on Montfaucon’s illustration of the same subject in his ‘Antiquities of France’, a copy of which Walpole kept in the Library at Strawberry Hill. When I consulted the 1842 Great Sale Catalogue, I learnt the buyer was William Seguier (1771-1843), the first keeper of the National Gallery. Where could Philip have got to now?

By the far the most important sourcebook in this investigation was to be the 1892 catalogue from the sale of the collection of Hollingworth Magniac (1786-1867). A merchant and connoisseur, Magniac made his fortune from the opium trade in China and used it to build one of the finest 19th century collections of medieval art, which he kept at Colworth House, Bedfordshire. I recalled that Magniac was particularly interested in objects with a Strawberry Hill provenance. In fact, several objects from his collection are now on view in the ‘Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill’ exhibition, among them a Vase with Arms and Ring Device of the Medici (now in the British Museum) and a Limousin Hunting Horn.

I knew I must consult the Magniac sale catalogue if I had any chance of resolving the Van Orley puzzle.

Carefully turning the pages in the hope of a glimpse of Philip, I came upon lot 76: ‘Portrait of the Emperor Charles V, by an early Flemish master on panel. This beautiful portrait, a head, of proportions considerably larger than life, represents Charles V at about seventeen or eighteen years old… Painted circa 1511… From Strawberry Hill Collection’. Right provenance and very nearly almost the right description. Wrong sitter. I felt deflated. The Magniac catalogue appeared to have failed me until I asked myself the deceptively simple question:

Could this have been the portrait Walpole perhaps wrongly identified as Philip?

I had to temporarily suspend my belief in Walpole’s infallible scholarship in order to consider the possibility. There was just one further reference I needed to consult to confirm my suspicions. I recalled the reference to Montfaucon and decided to examine the illustration of Philip myself in order to make a judgment. When I checked, I immediately understood Walpole’s mistake. Philip’s image in ‘Antiquities of France’ bore a striking resemblance to the young Charles V. It was Charles’ V portrait that I was chasing after all and a simple case of mistaken identity had led me astray.

With the sitter’s true identity confirmed, it took no time to locate the young emperor in Budapest’s Szepmuveszeti Museum, where he was transferred after 1896. After all, it is the only existing portrait of a young Charles V, which makes the work, together with its exceptional quality, such an important piece. How remarkable to think that even Walpole himself, guardian of such a trove of extraordinary treasures, never knew he possessed such a significant object in the history of Europe.

As with so many things in provenance research, sometimes it is just a matter of a microscopic detail that is the key to unlocking lost treasures within treasures.

We invite you to continue sleuthing and if you think you might have spotted one of Walpole’s missing gems let us know by emailing treasurehunt@strawberryhillhouse.org.uk.

Portrait of Charles V by Van Orley (inv.n. 1335)

Portrait of Prince Philip of Austria

Portrait of Prince Philip of Austria in Bernard Montfaucon in Les monuments de la monarchie française (for Henrik IV, vols. 1-5, Paris, 1729–1733)