Strawberry Hill House is internationally famous as Britain’s finest example of Georgian Gothic Revival architecture.

Did we find the lost Van Dyck?

Posted on 28 September, 2018

In this ninth instalment of our series on the Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill, art historian and provenance researcher Silvia Davoli makes another astonishing discovery. As the opening of the ‘Lost Treasures’ exhibition approaches, Silvia draws ever closer to fulfilling her quest to restore Horace Walpole’s extraordinary collection when she uncovers an original Van Dyck just over 100 miles from where it once resided at Walpole’s gothic villa.

One of Horace Walpole’s most beguiling qualities must be his fondness for ironic play. As I pore over the list of portraits that once hung in his great Gallery at Strawberry Hill, none of which he bore any family relation to, I think to myself that it must have tickled him to reproduce such a characteristic element of an English country house in his make-believe ancestral castle. How he must have revelled in curating this gallery full of ‘ancestors’. There was the once missing portrait of Marguerite de Valois, Duchess de Savoie by Antonis Mor, who I found after a serendipitous visit to the Warburg Institute. There the portrait of John, 2nd Baron of Sheffield who I traced to the London office of a member of the present-day Sheffield family. Finally, Walpole’s eyes may have come to rest on the doleful face of the Countess of Exeter.

Near completely buried beneath the weight of her black mourning robes, Frances Bridges is painted by Sir Anthony Van Dyck as an ageing widow. Completed in the 1630s, the somber portrait hung on the left-hand side of the chimney in Walpole’s Gallery, right by the Duchesse de Savoie and the Greek sculpture of an eagle found in the Roman gardens of Boccapadugli near the Baths of Caracalla. Only where was the mourning Countess now? I wondered, if like several bidders at the Great Sale of 1842, her descendants flocked to buy back their ancestor’s portrait and reposition her where she belonged: in an ancestral long gallery. To lift the veil on her disappearance, I knew I would need to investigate the circumstances of her acquisition by Walpole.

I soon learnt that Walpole took an interest in the exceptional art collection of fellow connoisseur Jonathan Richardson “the Elder” (1667-1745). An English artist, writer on art and collector of some 4,749 old master drawings, Richardson worked as a portrait painter in London and is considered by some as one of the three foremost painters of his time. Richardson believed that his Countess was an original painting by Van Dyck. Therefore, when Walpole purchased the Countess from Hudson, the painter and son-in-law of Richardson, for £32 in 1784, he was adding a valuable autograph work to his impressive collections.

‘Frances Bridges, daughter of the lord Chandos’, reads the entry in Walpole’s 1774 ‘Description of the Villa’. ‘Second wife of Thomas Cecil, earl of Exeter, on whose left hand she refused to lie on his tomb in Westminster-abbey’. The ‘Description of the Villa’ offered me a further tantalising insight into Van Dyck’s solemn-faced widow, which I could never have imagined: ‘This lady was most falsely accused of many crimes, of which she was entirely innocent, and acquitted’. I suddenly felt there was much more to this unassuming portrait and consulted a copy of Granger’s Biographical History of English Portraits to probe the accusations levied against the Countess. They had all the makings of a gothic horror novel.

The Countess was accused of incest with her son-in-law, Lord Ross, who married the daughter of Sir Thomas Lake, Secretary of State to James I of England. Her accusers, Lady Lake and Lady Ross, also claimed the Countess dabbled in witchcraft and sought to poison them to silence their accusations. Of course it is entirely speculative, but I could not help but imagine Walpole, author of the mysterious ‘Castle of Otranto’, a gothic ghost story inspired by a painting of Lord Falkland, which also hung in the Gallery at Strawberry Hill, was somehow moved to acquire the Countess in view of these wild tales of black magic and attempted murder.

Disappointingly, the 1842 Great Sale catalogue offered no further clues as to where the Van Dyck may have vanished to, beyond the buyer’s name, ‘Mr Thane’, an art dealer. I knew from experience that when the buyer is an art dealer, it is always very challenging to track the object down. I had to assume that this original work was lost to us and naturally this fuelled my longing to return the Countess to her former home in Twickenham. This was somewhat complicated by my discovery of two so-called copies of the portrait: one at Boughton House and the other at Hagley Hall

At first I thought the trail of the original work may be hidden in the catalogue records of the numerous sales in which the Countess changed private hands between 1842-1876. Following its acquisition by ‘Mr Thane’, the portrait eventually arrived in the private collection of Liet. Col. Francis Cunningham. I was delighted to discover that while in Cunningham’s possession, the portrait was viewed by George Scharf, first Director of London’s National Portrait Gallery, who was convinced the painting was an original Van Dyck. However, I stumbled on a roadblock as I could find no traces of this supposed original after Cunningham sold the work through Sotheby’s to a ‘Toone’ for £24 in 1876, as recorded on Yale University’s Lewis Walpole Library website. Who was this mysterious Toone? I could not find anything about them and feared the trail had gone cold.

Unwilling to surrender the hunt, I delved into the provenance of the Boughton and Hagley Countesses. A crucial piece of evidence allowed me to eliminate Hagley immediately. Their Countess was in situ prior to 1842, when ours was still enjoying the company of Walpole’s other ancestral portraits at Strawberry Hill. My finding reopened the question of the attribution of Boughton’s painting, which had undergone heavy restoration in the 1960s.

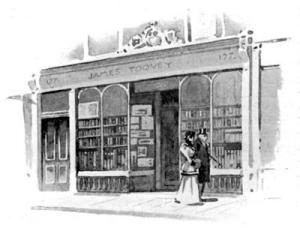

I resolved to consult the 1876 auctioneer copy of the Cunningham sale. To my great surprise, I immediately noticed that the buyer name signed next to the painting was not ‘Toone’ but ‘Toovey’. Mr J. Toovery (1814-1893) was one of the two great booksellers of Piccadilly at the time. Cunningham himself was after all a collector of books.

I could barely contain my joy after asking the very kind curator at Boughton House about the provenance of this painting and he replied “Our painting (No. 121), was purchased by the 3rd Marquess of Exeter (1825-1895) from a Mr. Toovey, of 177 Piccadilly, in December 1876”. What a superb discovery!

Another treasure restored and not a moment too soon with the launch of the exhibition ‘Lost Treasures of Strawberry Hill: Masterpieces from Horace Walpole’s Collection’ mere weeks away on 20 October 2018. Would you like to experience this unique moment in Strawberry Hill’s history for yourself? For the first time in over 170 years, Strawberry Hill will be seen as Walpole conceived it, with the collection in the interiors as he designed it, shown in their original positions.

Book your ticket here now and come and see some of the most important masterpieces in Horace Walpole’s collection for yourself at this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition.

Portrait of Frances Bridges, Duchess of Exeter

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) ?, 1630–39. Oil on canvas, 132 × 105.4 cm. The Burghley House Collection

Portrait of Frances Bridges, duchess

Copy after Van Dick, Hagley Hall

James Toovey

Shop of Mr J. Toovey at Piccadilly n.177

Van Dyck’s preparatory drawing at the British Museum