From the Houses of Parliament to Strawberry Hill

Written by Cas Bradbeer, Curatorial Assistant

In the second half of the 1850s, Frances, Countess Waldegrave (née Braham, 1821-1879) had amassed wealth sufficient to restore Strawberry Hill. Works were supervised by Mr Ritchie, the clerk of works to her husband, George Granville Harcourt (1785-1861). Harcourt had been Father of the House of Commons since 1850, during which time Minton tiles had been laid in the Houses of Parliament, designed by Augustus Pugin (1812-1852), the leading architect of the Gothic Revival during the Victorian period.

At least two of the tile designs (Figures 1 and 2) used by Lady Waldegrave in the Hall and Vestibule of Strawberry Hill were the same ones used in the Palace of Westminster. They were all designed by Pugin and manufactured by the Minton firm, which was founded in Stoke-on-Trent in the 1790s by Thomas Minton (1765-1836). By employing motifs from the Houses of Parliament, Lady Waldegrave indicated to her guests, upon first walking into the house, that this was a place for discussing matters of government. How fitting that it was during this period that she began hosting Liberal Party weekends at the house, welcoming the likes of prime ministers, royalty, and foreign diplomats to Strawberry Hill. To get a sense of the footfall these durable tiles were required to sustain, Lady Waldegrave’s parties were reported at the time to cause traffic jams all the way from Twickenham Station.

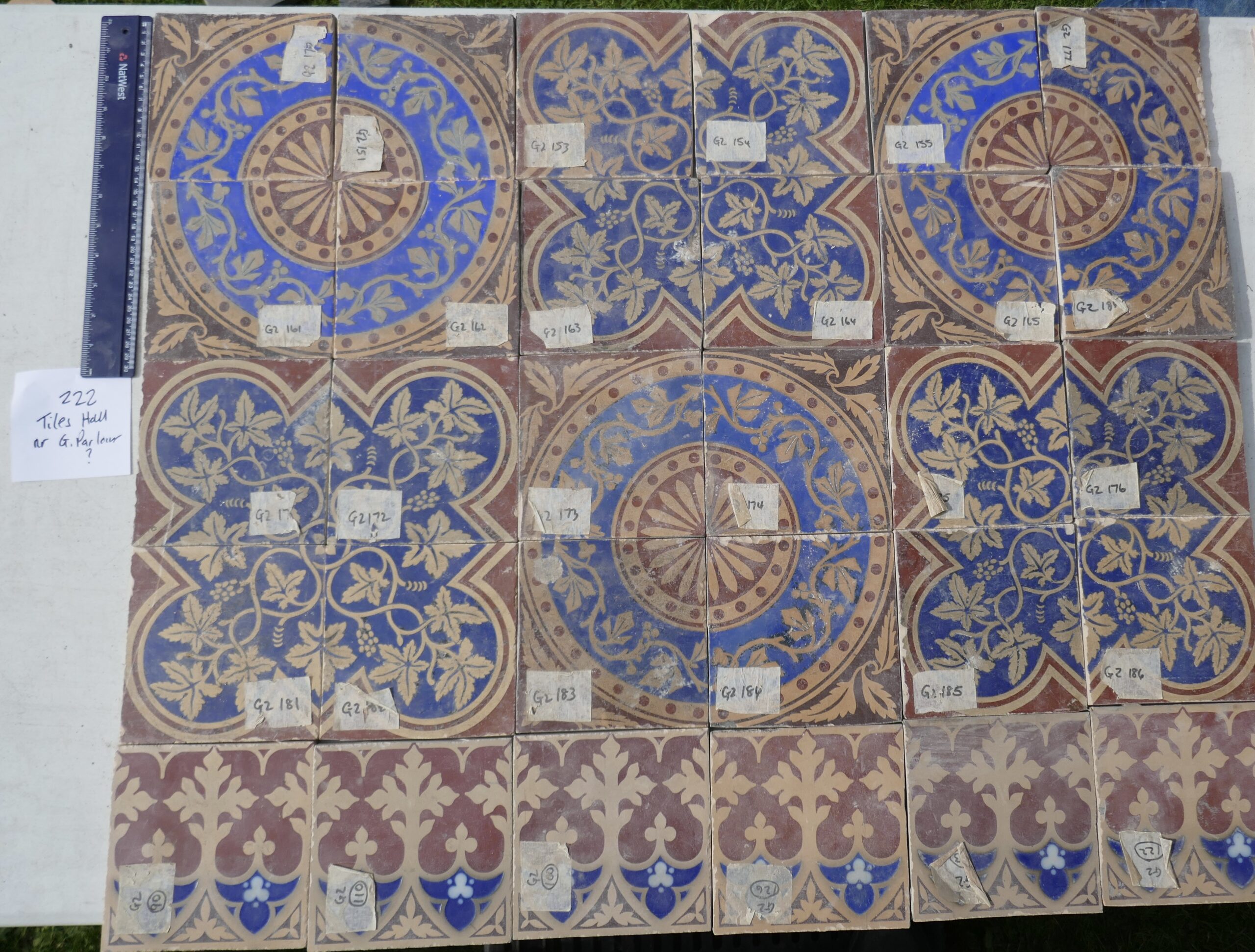

Employing about twenty patterns designed by Pugin, Lady Waldegrave installed three schemes of Minton tiles – one in the Hall (Figure 3) to replace Horace Walpole’s hexagonal red tiles, one in her newly constructed Vestibule (Figure 4) and one from an unknown location in the house (Figure 5). The Vestibule, a glass-covered entryway from the carriage drive to the Hall, was ridden with dry rot by the 1950s, and was demolished. It is unknown where these tiles went, but the Thomas Woolner sculpture installed by the Stern family (Lady Waldegrave’s successors at the house) was relocated to the Pantry. During the major restoration of the house in the 2000s, most of her tiles from the Hall were also relocated to the Pantry (Figure 6).

Minton was the most important ceramics factory during the Victorian period, under the stewardship of Thomas Minton’s son, Herbert Minton (1793-1858). He worked closely with Pugin, including collaborating on the creation of the Medieval Court at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Minton held the patent rights for a recently developed method of manufacturing encaustic tiles, a technique Pugin, a proponent of the Gothic Revival, was particularly interested in, since medieval churches were often decorated with colourful inlaid tiles. In 1842, Pugin wrote: ‘Unless [this method] be revived, our churches will never produce the rich and harmonious effect of the ancient ones’. In that same year, Minton sold his first commercial floor using Pugin’s designs in encaustic tiles.

Pugin popularised his designs to become mainstays of decorative arts in the period. His treatise on architecture and decoration, Floriated Ornament (1849), contains 33 pages of chromolithographs showing his patterns in which plants are flattened as they were in medieval designs, and as they are in the leaves and flowers of Lady Waldegrave’s tiles. This book went on to be a major influence on the Arts and Crafts movement. Pugin also helped introduce these designs into mainstream fashions by encouraging Minton to put some of his designs into general production, allowing them to be purchased for private homes such as Strawberry Hill. Pugin saw the restoration of these medieval-style encaustic tiles as an essential part of his revival of Gothic architecture, or ‘Christian’ architecture, as he preferred to call it. Minton continued to advertise the sale of Pugin’s designs for the Houses of Parliament for over twenty years after their completion.

Another way Minton’s tiles were popularised in this period was The Art Journal, which in 1851 dedicated five pages of coloured images of Minton tiles. However, these tiles featured his dust-pressing process, in contrast to the tiles that Lady Waldegrave purchased, which employed Minton’s ‘sandwich’ construction method using wet clay. The dust-pressing approach was transformational in terms of mass-production, using a technique patented by Richard Prosser in 1840 whereby clay was almost totally dried and ground up into a powder before being pressed by steel dies. This process took days to dry but Minton’s wet clay process took weeks and was more prone to warping.

As is evident by the edges of Lady Waldegrave’s tiles which feature a thick layer of red sandwiched between two thin layers of white (Figure 7), Minton used his ‘sandwich’ method for these, rather than the dust-pressing process which did not come into widespread use until about 1860. The tiles in our collection were made by sandwiching a layer of coarse and cheap clay between two slim layers of fine clay, the top layer of which was imprinted with the encaustic design using a machine press. A skilled craftsman poured slips (wet clay mixed to the consistency of cream), which were then scraped flat after a few days and left to dry for up to three weeks before firing. Upon arrival at Strawberry Hill, they were assembled into patterns and laid in a wet mortar screed.

The designs Lady Waldegrave chose were elsewhere employed in a range of public buildings through tiles of ‘sandwich’ construction. For example, the cross fleury in a blue quatrefoil with yellow rosettes in the red corner spandrels (Figure 8, centre left) was used in St Mary’s College in Birmingham and the parish church of Corfe Castle [see British Museum object numbered 1994,1003.4]. Pugin’s tiles were very popular in Victorian restorations of medieval churches like that of Corfe Castle, meaning Lady Waldegrave would have been acting in the tradition of Horace Walpole’s view of Strawberry Hill as a Gothic construction. Several other examples of these tile designs are currently on display at the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum [see British Museum object numbered 1980,0307.103.a-d and V&A object numbered C.188B-1977].

In 2024, our museum was awarded a Collections Access Grant by the Decorative Arts Society, which enabled our Collections Team to compile a digital inventory of the tiles on our TMS Collections catalogue. One of each design was selected for cleaning, using deionised water and microfiber cloths. These have been laid on acid-free tissue paper, where they are preserved in the museum for consultation by staff, volunteers and researchers, as well as being available for future displays. Each was photographed for our digital database and this webpage. A full list of tiles in our collection installed by Lady Waldegrave can be found in our project’s Highlights & Inventory document.

Minton wares abounded at Strawberry Hill beyond these tiles. Ample evidence of this can be found in an 1883 catalogue of the sale of goods left at Strawberry Hill after Lady Waldegrave’s death. The ceramics mentioned include over 400 items from Minton & Co, such as a china dinner service amounting to over 200 pieces. The tiles from the Vestibule and Hall were mentioned, but not available for sale, whereas over 100 Minton tiles were sold from Lady Waldegrave’s Stable Yard. The Stern family continued this tradition after purchasing the house, and in the 1923 catalogue of the Dowager Lady Michelham’s possessions here, several Minton objects appear, such as ‘A Minton oviform vase, with entwined snake handles, painted with a landscape and sheep, 22 in. high’. It would make a fascinating exhibition research project one day to try and track down the other Minton wares kept at the house, such as Lady Waldegrave’s ‘pair of Minton’s china swans’ and her ‘Minton’s ware centre case, 24-in high, with serpent handles and painted sheep in Winter Landscape, by W.[S.] Coleman’.

Sources

Fisher, Michael. Pugin’s Designs and Minton Tiles, presented at the Church Ceramics Conference of the Tiles & Architectural Ceramics Society, 2006.

Inskip & Jenkins. Restoration of Walpole’s Villa as a heritage site, Ground Floor, 2006.

Knight, Frank & Rutley. A Catalogue of the Contents of Strawberry Hill, by Direction of the Dowager Lady Michelham, 1923.

Ventom, Bull & Cooper. Strawberry Hill, A Catalogue of the Contents of the Mansion, 1883.

Figure 1. Tile, designed c.1847 by Augustus Pugin, made by Minton & Co, installed at Strawberry Hill by c.1856 by Lady Waldegrave.

Figure 2. Tile, designed by Augustus Pugin, made by Minton & Co, installed at Strawberry Hill c.1858 by Lady Waldegrave.

Figure 3. The Hall at Strawberry Hill, c.1990s.

Figure 4. Lady Waldegrave’s vestibule extending the covered main entrance to the driveway, c.1920s.

Figure 5. Tiles, designed by Augustus Pugin, made by Minton & Co, installed at Strawberry Hill c.1858 by Lady Waldegrave.

Figure 6. Pantry, photographed during an exhibition celebrating contributors to the restoration of Strawberry Hill.

Figure 7. Tile, designed by Augustus Pugin, made by Minton & Co, installed at Strawberry Hill c.1858 by Lady Waldegrave, being cleaned in this photo from 2024.

Figure 8. Tiles, assembled for cleaning during our cataloguing project funded by the Decorative Arts Society.

In 2024, the Collections Team at Strawberry Hill House conducted a cataloguing project to explore the our collections originating from the time of Lady Frances Waldegrave and the Stern family. Several blogs, a digital database, and a PDF illustrated inventory were produced, thanks to the Collections Access Grant provided by the Decorative Arts Society. FIND OUT MORE