The Lost Dagger of Henry VIII

Posted on February 28, 2018

In this second instalment of our special blog series, we continue to follow art historian and provenance researcher, Silvia Davoli’s quest to find the lost treasures of Strawberry Hill House. Formerly the home of Horace Walpole in the 18th century, Strawberry Hill House was emptied of Walpole’s celebrated art collection when it was scattered 200 years ago. Silvia is now sifting through archives and searching museums in every corner of the globe to uncover the lost treasures in a bid to restore them to Strawberry Hill. Can you help her in her quest?

Charles Kean turns the dagger over and over in his hands, rubies burn red like flames lapping at the handle. Visions of its former owner, Henry VIII leap into his imagination, the great mountain of a king cutting a monumental figure in ermine and gold brocade, bejewelled fist clasping a dagger as in the portrait after Hans Holbein the Younger.

Did Kean, the celebrated actor-manager, stand before his mirror, chin thrust out, chest puffed up under his smoking jacket clutching the dagger with Henry VIII’s nonchalance? Or did he draw it close to him, peering at it under the lamplight, gently rotating it to make the rubies dance like glowing embers? How did it come to be in his possession when it once formed part of Walpole’s astonishing collection and can I ever hope to restore it to its former home at Strawberry Hill House when it is has been missing for so many years?

I begin my hunt for the lost dagger by delving deeper into Walpole’s mysterious world and retracing its journey from King to collector and a tiny bijou room in Twickenham.

An Ottoman ceremonial dagger, it was once housed in the small first floor room at Strawberry Hill House known as ‘The Tribune’. With a spray of gilt ornamentation ambling up its stone grey walls like a floral creeper, it was used by Walpole to house his most magnificent treasures.

As I wander in I imagine the bronze sculptures after the antique Apollo Belvedere and Venus of Medici, once artfully arranged inside its niches, just as Walpole described in his inventory. I envisage the pietre dure casket on the altarpiece and the glass closet filled with Walpole’s ‘principal curiosities’. Most remarkable of all was the rosewood and ivory cabinet designed by Walpole himself and commissioned to house his inestimable collection of miniature portraits.

As I stand beneath the star-shaped skylight of yellow glass, which Walpole describes as having cast ‘a golden gloom all over the room’ I try to imagine the lost dagger in its former home.

Bought by Walpole from the sale of Lady Elisabeth Germaine (1680-1769) in 1770, the dagger is described in his inventory as ‘Henry 8th’s. dagger, of Turkish work, the blade… of steel damascened with gold, the case and handle of chalcedonyx, set with diamonds and many rubies’. Housed in the glass closet near one of the Tribune windows it must have sat glinting among countless treasures, perhaps somewhere between an agate oval casket and an antique figure of a muse cast in silver.

I imagine Walpole removing it from the display, running his fingers along the length of its richly inlaid blade, holding it up to the yellow light cast by the star in the centre of the ceiling and basking in the kingly splendour radiating from the gems set in its hilt. Where could this magnificent object have disappeared to ? I leave the Tribune and go in search of any crumbs scattered by the dagger’s next owner, which might enable me to pick up the trail.

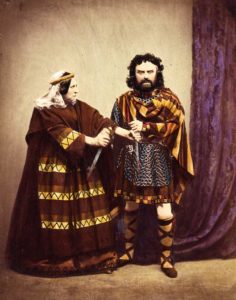

Charles Kean (1811-1868) considered himself a historian actor and avidly collected historical memorabilia and costumes. He was also a theatre manager famed for staging a series of Shakespearean revivals during his tenure at London’s Princess Theatre from 1850-59. ‘Never unaware of his sober responsibilities as a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries’, Kean strove for accuracy in every detail of his productions, dressing his actors in lavish historical costume and placing them in authentic settings crammed with archaeological detail.

Given his tireless commitment to pictorial realism, I am unsurprised to discover that it was Kean who leapt at the chance to purchase the Ottoman dagger when it appeared at Strawberry Hill’s Great Sale of 1842, together with Cardinal Wolsey’s red felt and silk hat. Who better than Kean to appreciate its exquisite embellishment and to honour its supposedly royal provenance? After all, Kean himself staged a production of Henry VIII. The set designs are now held in the Theatre and Performance collections of the V&A.

I am charged with excitement at my latest discovery and buoyed by the possibility that I might be one step closer to locating the dagger. Wolsey’s 16th century hat has resurfaced in the collection of Christ Church, Oxford University. Surely the dagger can be retraced just as easily?

Unfortunately, the trail quickly grows cold. I learn that upon Kean’s death the dagger is sold for £215 by Christie’s in 1898 to a ‘Haigham’. Or is it ‘Heigham’? Possibly even ‘Heijham’. Who was the mystery buyer and where has he or she squirrelled away Walpole’s dagger? Perhaps it now resides with a wealthy sheikh in Dubai providing a breathtaking centrepiece for his private collection. I wonder if the key to unearthing its location is in its striking similarity to another dagger now on display in the Harley Gallery at Welbeck.

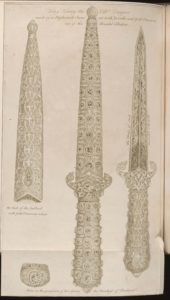

Undeterred by the fact that the dagger was last seen in 1898, I begin to study engravings, which reveal a remarkable resemblance between Walpole’s dagger and that of another held in the collection of Margaret, Duchess of Portland. I learn that the Portland dagger was purchased by Edward Harley (later the 2nd Earl of Oxford) in 1720 from the collection of Thomas Edward, Earl of Arundel (1586-1646). I think I am onto something extraordinary.

The Arundel collection is the very same collection that Walpole’s dagger is believed to have originated from. Even more extraordinary is the fact that an engraving of the Portland dagger by George Vertue from 1749 refers to a provenance from Henry VIII. I further learn that both daggers are traditionally thought to come from Henry VIII’s collection due to their similarity to a more richly decorated dagger described in the 1547 inventories of the late king’s possessions.

Spurred on by these remarkable connections I decide to approach the V&A’s curator of Ottoman Art, Tim Stanley, and curator of the Welbeck Collection, Gareth Hughes. They do not disappoint. I am astounded to discover that a third exemplar of a dagger similar to both the Portland and Walpole daggers has emerged from within the collections of the Royal Armoury in Vienna. Immediately I write to the curator there and I await his response.

Meanwhile, my list of clues grows as I draw more and more connections between the lost and found daggers:

1. Both the Walpole and Portland daggers are strikingly similar in their appearance;

2. Both are said to originate from Arundel’s collection;

3. Both are linked to Henry VIII; and

4. Both are part of a small and distinctive group of Turkish or Persian daggers dating to the second half of the 16th century.

The Portland dagger’s blade is thought to be 16th century Iranian, the hilt and scabbard early 17th century Turkish. Is this then where I need to direct my investigations? It is not inconceivable to suggest Walpole’s dagger has long disappeared from British shores and returned to its ancestral home in North Africa or the Middle East. Perhaps as I write our sheikh is admiring the damascened steel and the rubies winking at him from his own purpose-built cabinet of curiosities in a 21st century Tribune.

Could the trail be heating up again?

Perhaps you could help me solve the mystery. You could start right now by searching on your computer or smartphone:

1. Try performing a Google search for similar daggers

2. Trawl sale records online on the Blouin Art Sales Index, Christie’s auction results or Sotheby’s Sold Lot Archive for any sale record of the dagger

3. Browse genealogy websites for ‘Haigham’

Good luck and don’t forget to get in touch with your findings via treasurehunt@strawberryhillhouse.org.uk. Together, we might bring back Walpole’s dagger to Strawberry Hill.

Boodle Hatfield, solicitors is delighted to be sponsoring the Strawberry Hill Treasure Hunt blog.

Portrait of Henry VIII by the workshop of Hans Holbein the Younger.1497/8 (German).

John Carter, Henry VIII’s dagger, ink and wash and watercolour, c.1788. The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

John Carter, The Tribune at Strawberry Hill, c. 1789. The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Charles Kean and his wife as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, in costumes that aimed to be historically accurate (1858).

The red hat of Cardinal Wolsey, 16th century, felt, silk, D. 47 cm. Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford University.

Henry the VIII dagger, engraving by George Vertue, 1749. The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

A dagger, traditionally called Henry VIII’s dagger, Turkish C17, the blade possibly Iranian, C16. Hilt and scabbard of white jade decorated with hessonite garnets in gold settings. The Portland/Arundel dagger will be on display from late May this year. The Portland Collection, Harley Gallery, Welbeck Estate, Nottinghamshire / Bridgeman Images.