Walpole and the Ancient World

Posted on April 30, 2018

In this fourth instalment of our special blog series, we continue to follow art historian and provenance researcher, Silvia Davoli, on the trail of the lost treasures of Strawberry Hill House. Silvia unearths some astonishing finds when she delves deeper into Walpole’s collection of antique artefacts and explores his fascination with the ancient world.

Rome, February 1740. A young Horace Walpole arrives and I imagine the late winter sun illuminating his face, earnest and flushed with anticipation as he trawls the city for fashionable parties and collectible antiques.

So far, my research has enabled me to build a colourful portrait of the man as prolific writer, curious collector, gothic romantic. Yet up until now the antiquarian and his fascination with ancient Greece and Rome has remained largely unexplored by myself or any other historian. This despite the fact the Strawberry Hill heaved with antiquities: ossuaria, a series of Emperor busts in the great Gallery, cameos, intaglios, the great Roman Imperial Eagle, a gold miniature of a Roman lady and her son, bronze ewers and vases, a muse cast in silver, all scattered around the house.

As a young Grand Tourist, Walpole’s voracious appetite for the antique lead him to collect coins, statuettes, medals, vases. Everyday objects that could tell him more about the daily habits and style of ancient Romans than great statues or monuments. Walpole as antiquarian was supported in his quest by friends based in Italy such as Horace Mann, the British Envoy in Florence, and William Hamilton in Naples.

He would go on to acquire the Imperial Eagle and its altarpiece from the Roman gardens of Boccapadugli near the Baths of Caracalla. Displayed on the left hand side of the chimney in the great Gallery, ‘the boldness and yet great finishing of this statue’, Walpole writes in his 1774 inventory, ‘are incomparable; the eyes inimitable’. He also bought the collection of Conyers Middleton, an English clergyman and author of ‘Life of Cicero’ (1741). Middleton, like Walpole, in typically antiquarian fashion, was captivated by the everyday objects of the ancients.

Walpole’s gothic castle brimmed with antique treasures and yet very little in the way of research has been completed on his antiquarian endeavours. I wonder if perhaps this is because it was a typical virtuoso collection of small artefacts, not scene-stealing monolithic sculptures. Although detailed documentation of his antiquities abounds including the fantastic illustrations in Middleton’s book ‘Germana quaedam Antiquitatis erudiate Monumenta quibus Romanorum veterum Ritus varii’ (1745), historians have made very little of these fine records.

I recognised them for the gems they were: vital clues in my hunt for the lost treasures of Strawberry Hill.

I began methodically, gathering up all the images I could find of Walpole’s antiquities. Assembling all the details of where and when Walpole bought them as recorded in his correspondence, I even extracted all the references to Walpole’s taste for the antique I could find in Frances Haskell and Nicholas Penny’s ‘Taste and the Antique’ (1981). Two of Walpole’s objects in particular attracted my attention:

1. A detached Roman fresco of River Gods;

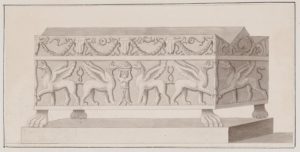

2. An antique marble sarcophagus on lion’s paw feet.

Once hung above the door in Walpole’s Little Library in his garden cottage at Strawberry Hill, the fresco was bought by Walpole from Middleton’s collection. I uncovered a drawing of the fresco in Middleton’s 1745 ‘Germana’, which finely illustrates the head of a woman crowned with flowers floating above an ancient gathering of men. It was sold as lot 96 on day 19 of the Great Sale of 1842 to a ‘C. Wentworth Dilke Esq’ for £7.70.

Despite the myriad and high quality visual and literary sources I had to hand, I hit a roadblock. I could not track down either piece nor in fact any other antique object from Walpole’s collection. Determined not to let this hiccup derail me I resolved that my fortunes would soon shift. After all, the provenance researcher’s work is so often guided by serendipitous events. In fact, it was Walpole himself who coined the term serendipity.

The turning point came when I met Dr Florent Heintz, Head of the Department of Ancient Sculpture and Works of Art at Sotheby’s. A brilliant scholar, a mine of information and a veritable champion of provenance research, Dr Heintz has been a critical guide to me on the trail of Walpole’s antiquities. Hoping to glean any further information on the possible whereabouts of the missing fresco I sent Dr Heintz some images of Middleton’s illustration. His response floored me.

Just two weeks before I sent Dr Heintz the drawing, a Sotheby’s client brought a piece of Grand Tour souvenir into their New York offices. It was in fact a Roman fresco on stucco, ca. 2nd century CE, with 18th century restorations, which perfectly mirrored Middleton and Walpole’s. I marvelled at the serendipity. Without the Middleton/Walpole provenance, the New York fresco might have been overlooked as mostly uninteresting Grand Tour memorabilia. Instead, I had happened upon one of our missing treasures.

Could I possibly hope to make a similarly fortuitous discovery in my search for the sarcophagus? Surely my luck had run out. The description in the 1842 sale catalogue reads: ‘A magnificent 3 feet 10 inches Antique Marble Sarcophagus, carved in the finest manner, with sphinxes, festoons… on lion’s paw feet’. Bought by Walpole from the sale of antiquary and collector, Fairfax Bryan Esq. (1676-1749), it was once situated in the pleasure ground gardens of Strawberry Hill. Despite research undertaken by some of the Friends of Strawberry Hill, all traces of the piece had been lost.

Stumbling towards yet another roadblock, I consulted Dr Heintz. Together we studied an illustration of the sarcophagus completed by George Perfect Harding at Strawberry Hill in ca. 1800 and held in the collection of the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University. With his vast knowledge and talent for research I should not have been surprised when Dr Heintz once again managed to find the missing piece of the puzzle.

He directed me towards the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Therein lay our lost treasure, bas-reliefs of sphinxes and all, just as the 1842 catalogue described it.

My findings, though hard-won, energised me even further in my hunt for Walpole’s lost treasures. They reinvigorated my desire to more deeply research Walpole’s fascination with the antique, which forms the subject of a forthcoming article I am working on with a colleague on the Middleton and Walpole collections of antiquities.

Though Walpole’s collection of ancient ornaments might have been historically dismissed as worthless trinkets lost in the shadow of monumental Roman sculptures and Greek statues, it has revealed ever more to me about the intellectual pursuits of the 18th century antiquarian. I believe the more I can get inside the great mind of the man perhaps the closer I will come to completely restoring his astonishing collection. But I still need your help.

Have you found any trace of our missing treasures? It is not too late to begin now. Start here by searching Middleton’s remarkable collection as documented in his ‘Germana’, all eventually purchased by Walpole. Good luck and don’t forget to get in touch with your discoveries via treasurehunt@strawberryhillhouse.org.uk.